Despite its significant role in economics and society as a whole, inflation remains a largely mysterious and confusing concept.

Inflation is the rate at which goods and services prices go up. Another way to look at this is the rate at which a currency depreciates in value. This means that your one dollar today will afford you fewer goods and services in the future.

Defining inflation is one thing; controlling it is another.

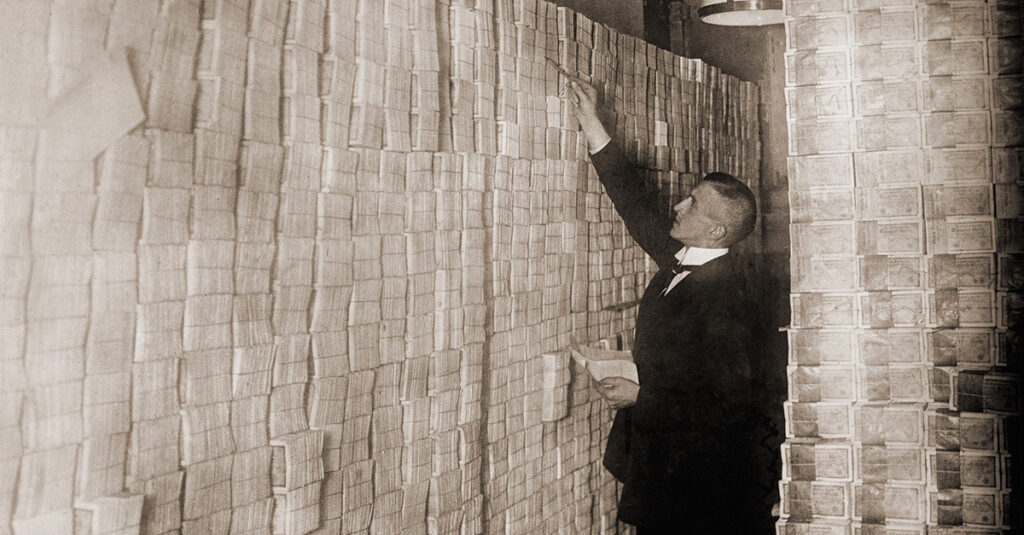

History has shown us how devastating the impact of high inflation can be. The Weimar Republic’s period of hyperinflation between 1921-1923 saw millions of people watch their life savings become worthless in a matter of months, leaving them without the means to afford even the most basic of food supplies.[1] In more recent times, Zimbabwe experienced runaway inflation that led to the prices of goods doubling every single day.[2]

These are extreme examples, and while today’s conditions don’t come close to this, we are, statistically speaking, currently living through one of the highest rates of inflation in modern times.

But what does this mean?

During periods of high inflation, the purchasing power of consumers decreases. That is, the income you generate can afford you fewer things. It also reduces the value of your cash savings. This impacts lower-income households disproportionately more because as their disposable income is decreased, they often have fewer options to reduce their outgoings. Essential goods and services, like electricity and food, are often the first to rise in price, while the interest payments on existing debt – like mortgages – will often rise dramatically as a result of central banks trying to tame inflation.

The increase in the cost of debt isn’t a direct consequence of inflation, but a natural result of the fight to bring down inflation. This comes as central banks, like the Federal Reserve or the Bank of England, increase interest rates. We’re seeing this play out right now with central banks worldwide increasing rates at an accelerated pace to fight inflation.[3]

Central banks raise interest rates in order to slow economic growth (yes, you read that correctly). The interest rate issued by central banks, often referred to as the bank rate,[4] is the rate at which they lend money to domestic banks. This rate influences the interest rate that those domestic banks will charge to lend money to consumers and businesses. As the bank rate increases, so will mortgage rates. As the cost of capital increases for businesses, their existing profit margins will be squeezed and they’ll have fewer options for investing in future business growth. As the cost of mortgages increases, consumers will have less disposable income so will reduce their spending.

This slows down economic growth.

As spending decreases, businesses lack the ability to increase the prices of their goods and services. As the profits of companies decrease, so does the wage growth of employees, leading to an increase in unemployment. What all of this results in is the rate of inflation slowing.

The challenge that central banks face is to slow economic growth enough to tame inflation without slowing it so much that it has damaging long-term effects on the economy. When you consider that one of the main measures of inflation, the consumer price index (CPI), is a lagging indicator,[5] you’ll realise that striking the aforementioned balance becomes even more difficult. Central banks only know that they’ve gone too far (or not far enough) with their rate increases when it’s too late. This is why the target for inflation is 2% and not zero. It gives a healthy buffer within.

Much of the discussion today centers around whether we will have a hard or soft landing from the current period of high inflation. In the UK’s case, this is largely a question of how long the recession will last as opposed to whether we’ll have a recession at all.

Going too far with interest rate hikes can lead to deflation, which is arguably much worse than high inflation. This is when the value of your money increases in comparison to goods and services. At first glance, this sounds pretty good, but when you realize that this means all of the assets you hold, like your home, are actually decreasing in value while any debt on them remains unchanged, it doesn’t sound so good. It also gives rise to a reduction in consumer spending. If you know that the value of something you’re looking to purchase will reduce in cost in a month’s time, you’re much more likely to save your money than spend it. This lack of spending cripples businesses, leading to lower wages and huge increases in unemployment.

As unemployment takes hold, consumer spending reduces further. In fact, within the first year of unemployment, consumption expenditures drop on average by 26.3%.[6] This doom spiral only perpetuates the problem further.

At this point, central banks will begin to reduce interest rates in order to stimulate economic growth. As interest rates lower, the cost of capital decreases and debt becomes cheaper. This positively impacts businesses because they can receive much-needed funding to survive and eventually grow. It helps consumers because their debt repayments reduce, unemployment reduces (as businesses begin hiring again) and disposable income grows, leading to increased consumer spending.

In March 2020, when the full gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, the Federal Reserve reduced its bank rate to close to 0% from 1.5%‑1.75%.[7] The Bank of England acted similarly, reducing rates to 0.1%,[8] the lowest rate in history.

Chart source data[11]

Fast forward to December 2022 and things couldn’t be more different. Today, the Federal Reserve announced another increase in their bank rate, this time by a rate of 0.50%, following four successive increases of 0.75%. This brings the rate up to a range of 4.25% and 4.5%,[9] which is likely to peak next year just above 5%.[10] The Bank of England’s bank rate currently sits at 3%,[11] with more increases to come.

Printing Money

There’s another role that central banks play in the creation of inflation: quantitative easing. This is where they issue new currency (also known as “printing money”), expanding the supply of money in the process, to purchase government bonds and other financial assets.[12]

The idea behind this is that this injection of capital into the economy will stimulate growth. Governments have more capital to invest in infrastructure, while companies and other financial institutions have more capital to invest.

Central Banks have grown rather fond of quantitative easing, and even during high inflation periods, they’ve continued to increase the supply of money. The side effect of continuously increasing the supply of money is that it depreciates its value if demand doesn’t increase in line with it. The more British pounds that are created out of thin air, the less each of those pounds is worth.

Chart source data[12]

Between November 2009 and 2020, the Bank of England printed £895 billion through their quantitative easing program.[12] While the extent to which quantitative easing contributes to inflation is a constant source of debate,[13] history has shown us that growing the money supply of an economy at an ever-increasing rate has an undeniable link to inflation.

Alongside monetary policy, there’s fiscal policy.

Fiscal policy is how the government play a role in influencing the economy, primarily through spending and taxation. Changes to the rates of taxation on businesses and individuals has an impact on economic growth, which in turn has an effect on inflation.

The complete meltdown of the British government during Liz Truss’s now infamous and record-setting brief tenure as Prime Minister is a perfect illustration of this. While most were calling for fiscal tightening, Truss and Kwarteng, the Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time, delivered a “mini budget” that sent shockwaves through the global economy.[17] Widespread taxation cuts and huge increases in borrowing sparked major concerns on the negative impact this would have on tackling inflation and contributing to future economic pain.

The fact that the UK government were taking the complete opposite stance to the Bank of England highlights is a perfect illustration of how fiscal and monetary policy can butt heads and cause volatility in the markets.

Taking Our Medicine

The reality is that the causes of inflation are nuanced, dynamic and complex. Simply stating that the expansion of the money supply is the cause of inflation would be inaccurate.

What got us to where we are today is a whole host of overlapping circumstances; some were preventable, and others weren’t. The unprecedented situation of facing a global pandemic and the impact this had on consumer spending, supply chain dynamics, and the need for copious amounts of stimulus spending is something that’s very difficult to prepare for.

The energy crisis in Europe that’s come as a result of Russia’s war on Ukraine has impacted inflation – in particular on fuel costs – is disproportionately growing inflation at a rate much faster than in the US.[13]

Chart source data[16]

While headline inflation is starting to slow in both Europe and the US,[15] further interest rate increases are coming next year, and even then, getting inflation under control is just one part of the battle. After this, attention will shift to the slowdown in economic growth.

This is one of the reasons why tackling inflation is so painful: it means things need to get much worse for people before they can get better.

- Fergusson, A. (1975) When money dies: The nightmare of the weimar collapse. London: Kimber.

- Uchoa, P. (2018) How do you solve catastrophic hyperinflation?, BBC News. BBC. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Coulton, B. (2022) Global Interest Rates Rising Faster than Expected, Pivot Unlikely in 2023, Fitch Ratings: Credit Ratings & Analysis for Financial Markets. Fitch Ratings. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Kenton, W. (2022) Bank rate: Definition, how it works, types, and example, Investopedia. Investopedia. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Britzman, M. (2022) Lagging vs. leading indicators – what’s the difference and what investors need to know, Hargreaves Lansdown. Hargreaves Lansdown. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Kolsrud, J. et al. (2018) “The optimal timing of unemployment benefits: Theory and evidence from Sweden,” American Economic Review, 108(4-5), pp. 985–1033.

- Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement (2020) Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Board. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Bank rate reduced to 0.1% and asset purchases increased by £200bn – march 2020 (2020) Bank of England. Bank of England. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Person and Howard Schneider, A.S. (2022) Fed’s Powell says inflation battle not won, more rate hikes coming, Reuters. Thomson Reuters. (Accessed: December 15, 2022).

- Smith, C. (2022) Fed set to slow rate rises but signal tightening not over yet, The Financial Times. Financial Times. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Official Bank Rate History (no date) Bank of England. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Quantitative easing (2022) Bank of England. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Greenlaw, S.A. and Taylor, T. (2015) “11.4 The Phillips Curve,” in Principles of Macroeconomics for AP courses. Houston, Texas: OpenStax.

- Elliott, L. (2022) Russian war slowing growth and hiking inflation, European Commission warns, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Irwin, N. and Brown, C. (2022) Inflation cools in November for the second-straight month, Axios. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Inflation rate: World (no date) Inflation Rate – Countries – List | World. Trading Economics. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).

- Heale, J. and Cole, H. (2022) How Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget turned into a major disaster, News | The Times. The Times. (Accessed: December 14, 2022).